- Mike Nelson

- From Whitetales

- Hits: 3092

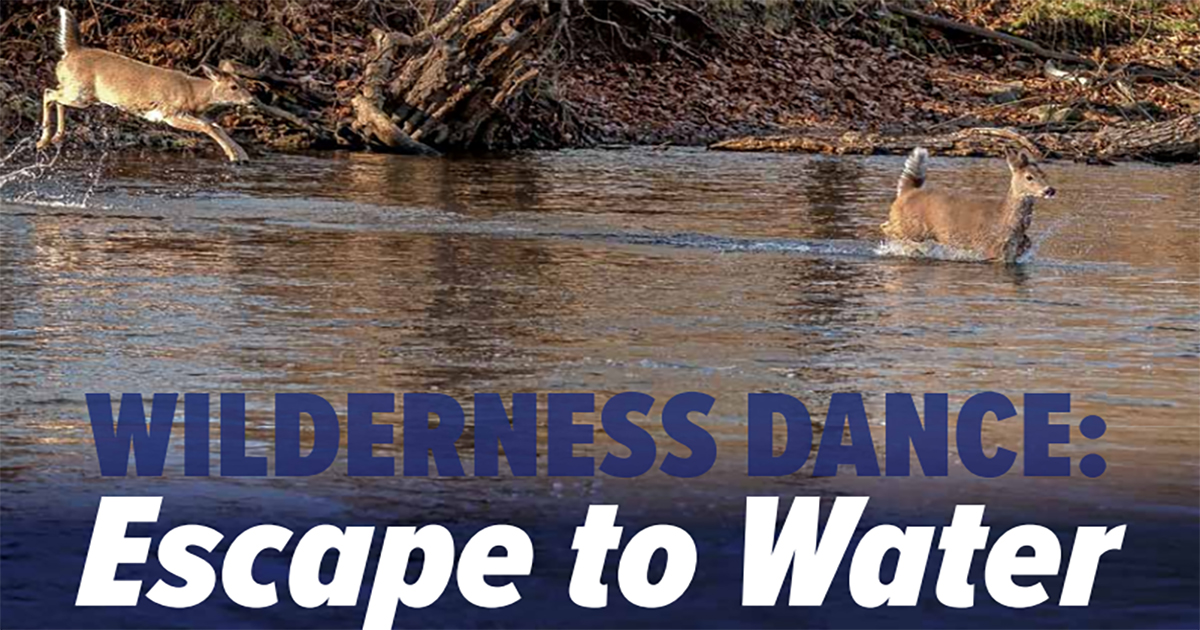

Wilderness Dance: Escape to Water

- Mike Nelson

- From Whitetales

- Hits: 3092

Biologists and the public have observed deer, moose, elk, and caribou escape into lakes, rivers, and ponds when chased by wolves. Deer did this throughout the year in the Boundary Waters Wilderness Canoe Area (BWWCA). Such escape opportunities for deer, however, were rare in winter when lake and river surfaces were frozen, except for those places where currents kept water from freezing.

Thomas Lake Swim

As my pilot and I flew toward Thomas Lake in November, the water in and around small bays, islands, and peninsulas appeared frozen or had some shore ice, but the main lake remained open. Reaching the lake, I spotted an object in the water far from shore. Dropping down for a closer look, a doe’s head appeared above the surface and its body just under the surface but visible from above. The doe swam rapidly as seven wolves traveled along the shore, apparently anticipating where the swimming doe might come ashore.

When 100 yards from the shoreline, the doe turned back toward the main lake, presumably detecting the wolves blocking her escape. Anticipating no immediate outcome, we continued to radio-track other packs nearby. Returning four hours later, we found the doe swimming in the same bay and the wolves watching from the nearest shoreline. As the doe swam 75 yards from the shore, a single wolf entered the lake and swam 25 yards toward her before turning around. The doe then started swimming parallel to shore toward an island 400 yards away, undoubtably looking for an escape route. The wolves also headed along the shore in the general direction of the island, connected to the mainland by 100 yards of new ice. On reaching the island the doe stood in the shallows close to shore, appearing exhausted from swimming. Meanwhile, the wolves stealthily crossed to the island on the narrow bridge of the new ice and approached the doe’s position, only to witness her once again swim away into deeper water. In a repeat performance, one wolf swam after her, this time for 50 yards before returning to shore to join its pack members observing from the shore.

We again departed for a half hour and upon our return found the doe swimming toward the same island and the wolves also returning to it. She stood in the shallows again when reaching the island, but this time she rested in front of a rocky incline or ledge closer to the water. The wolves approached the doe, concealed from her by higher ground and trees close to the shoreline. When the wolves reached within 25 yards of the doe, she bounded into the lake followed by a single wolf in full stride as it went airborne into the lake. It landed with a large splash as if launched from the ledge behind her.

The wolf swam up to the escaping doe 75 yards from shore and struggled to grab her head and neck while they were both swimming. Meanwhile, two wolves joined in, twice swimming out toward the pair at different times, one of them returning when only 10 yards from shore. The two wolves attacked the swimming doe for a minute, but then one returned to shore. The remaining swimming wolf continued to attack and finally gripped the doe’s neck, killing her while both were swimming, 10 minutes after she last swam to the island. The wolf that killed the doe towed her to shore, still gripping her neck while the other pack members waited on shore with tails wagging, anxious for the delivered meal.

The doe’s death came four hours after I first found her swimming in Thomas Lake. Although I had been gone much of that time, it was likely the doe was swimming most of the time based on her behavior earlier. She and the wolves were in the same bay where I first observed them, and the wolves persisted in not letting the doe escape to shore. It is unknown how long the wolves pursued her before she entered the lake, so the duration of the encounter is only a recorded minimum. The doe succeeded in delaying the wolves’ efforts, but her waning endurance from swimming and her inability to find shoreline free of waiting wolves finally ended her life. Had she swum continuously away from the bay and across the lake, she could have found a shoreline beyond the wolves’ easy reach. I can only guess that from the lake’s surface, a distant safe shoreline was beyond her view and that kept her in the bay. It remains unknown how often deer escape wolves by entering lakes when fleeing from wolves.

Stony River Chase

On the Stony River in January when 12 inches of snow covered the ground and the lakes were frozen, eight wolves traveling in timber approached the unfrozen shallow rapids where the river exits Slate Lake. Reaching the river on the north side, three wolves slowly moved onto the ice-covered bay near the rapids. They hesitated and soon turned back into the timber. I recognized their hesitation. In a previous winter on the Stony River, I skied to a deer killed by the same pack. Cautiously skiing on the ice near shore, I crowded overhanging alders within an arm’s length. Suddenly, the ice under my right ski gave way, and I instinctively shifted my weight to the left ski as flowing water appeared under my now suspended right ski. I leaned into the alders, dragging myself sideways to safety on unbroken ice, learning wolf knowledge firsthand.

Seconds after the three wolves retreated to shore, a large wolf in the woods bolted toward the rapids where a deer bounded 25 yards across to the south bank and turned downstream, paralleling the river. Three wolves splashed across the rapids following the running deer 100 yards ahead of them, both deer and wolves in full stride. After a half mile, the snow-covered and frozen section of the river narrowed to 20 yards where a small treeless island divided the river’s current and formed a shallow unfrozen pool between the north bank and the island.

The deer crossed back to the north bank on the ice just downstream from the unfrozen water and entered it. A minute later the lead wolf crossed the river at the same spot and approached the deer as it stood in shallow water. As the wolf reached the water’s edge, the deer charged it, striking out with its front legs, and driving the wolf back a few yards toward the shore. The wolf momentarily stopped, but then repeated its approach a second time. My next view as the plane banked sharply was that of the wolf gripping the deer’s head while pulling it onto the ice attached to the shore. The deer, still upright and resisting, dragged the wolf back to the edge of the water where the deer fell into the water, free of the wolf’s grip. The other two wolves in the chase stood on the south bank of the river appearing hesitant to cross on the ice. They may have been unaware of the struggle, their sight blocked by brush on the island. They finally crossed and joined the lead wolf in staring at the deer still standing in the shallow water after escaping the pursuing wolf’s grip. After a minute or two of staring at the deer, the wolves started to leave the scene as a fourth wolf approached them from the woods. The original three wolves continued walking away, but the new wolf stood and watched the deer for a few more minutes before also leaving, hesitant perhaps after seeing the previous struggle.

With the chase over, I continued radio-tracking other wolves. We circled the scene a half hour later and found the pack a half mile away and counted eleven wolves. Back at the island, the deer was gone, and I saw no blood or kill remains at the site. Apparently, the resolute deer withstood the attack. The combination of water and aggressive behavior certainly saved the deer from the jaws of the attacking wolves, at least for that moment.

Bogberry Lake Struggle

Wolves use their powerful jaws and teeth to bring down deer. In extraordinary and vivid detail, I watched a single wolf attack an adult buck while they both slipped on bare ice in early November when a few inches of snow covered the ground and when bucks were in prime condition at the beginning of the annual breeding season. While flying to locate the Gabbro Lake Pack, I saw two shapes appear on Bogberry Lake. Expecting to see two wolves from the Gabbro Lake Pack, instead, the lone alpha female wolf of the pack tried her best to kill a large-antlered buck, and the buck tried his best to avoid that fate. The wolf’s instinct and experience recognized the buck’s vulnerability to being caught even though no blood yet appeared on the ice. The scene played out in the slow motion of exhaustion by both the deer and the wolf. The buck attempted desperately to escape by moving forward, but his hooves slid on the nearly bare ice. Trying to move, his hooves only gripped the ice for a few yards before he sat down for a few minutes. The wolf joined him in this repose by resting on her chest with front legs stretched forward on the ice within inches behind the buck. The two repeated this pattern as the buck managed to stand and move forward a few sliding steps at a time. The wolf tried moving near the head of the resting buck, but the buck responded by turning and pointing his antlers toward the wolf in an instinctive defensive response to danger. After returning to the rear of the buck, the wolf gripped a hind leg, but that had no immediate lethal effect upon the large buck. At a moment when both rested again in a sitting position, the wolf appeared to rest her head on the buck’s hind quarters. The buck responded by turning his head and pointing his antlers toward her again, another attempt to deflect the wolf. The buck and wolf repeated slowly rising, awkwardly slipping, and eventually sitting several times while moving 500 yards across the lake. Eventually the exhausted buck could no longer rise and respond to the wolf’s attack, his life ending there on the ice.

I walked into the kill site the following day. The grey overcast skies advertised that more snow was coming, and I wanted to be sure I could examine the kill before it disappeared under a blanket of snow. I carefully crossed the recently formed ice, chopping holes to test its thickness for safe travel. Approaching the remains of the kill I could see most of the buck had been eaten, but the entire neck and head remained to be consumed. Blood-soaked ice, stomach contents, and hair created a faint red-brown appearance a few yards around the kill in contrast to the surrounding white-blue surface of the lake. The wolves had marked their ownership of the kill by leaving scats and urine on the ice, and ravens left their tracks and droppings as they claimed their portions of the kill. I suspected the wolves were nearby, waiting to finish the remains of the kill, including cracking open the skull and hip bones to reach all the edible parts of the buck. Having recorded the kill for science, I walked away, knowing that within a few days all the evidence of it would disappear into the landscape.

I never knew how the buck ended up on the ice rather than escaping on the firm footing in the woods. However, the known facts gave insight to deer life among wolves. The buck’s large size and impressive antlers suggested he was likely a strong competitor among other bucks for breeding access to does. Despite this, he became extremely vulnerable on the bare ice and ended life using his antlers as a last defense against a single wolf. The manner of his death during the brief period when autumn first turned to winter was a rare event during a short period before snow accumulated on frozen lakes providing more traction for deer to run.

Part 3 of “Wilderness Dance” in the next Whitetales issue concludes this enduring biological legacy with the effect of deep snow on deer ability to escape wolves, and aggressive deer posture deflecting wolves.

Michael E. Nelson (Ph.D.) is a retired wildlife research biologist and field supervisor for the U.S. Geological Survey wolf research in northeastern Minnesota. Based at Kawishiwi Field Lab in Ely, MN since 1974, he studied deer and their interactions with wolves for 36 years. His research and publications examined deer movements, survival, population dynamics, social relationships, genetics, spatial ecology, and deer-wolf relationships.